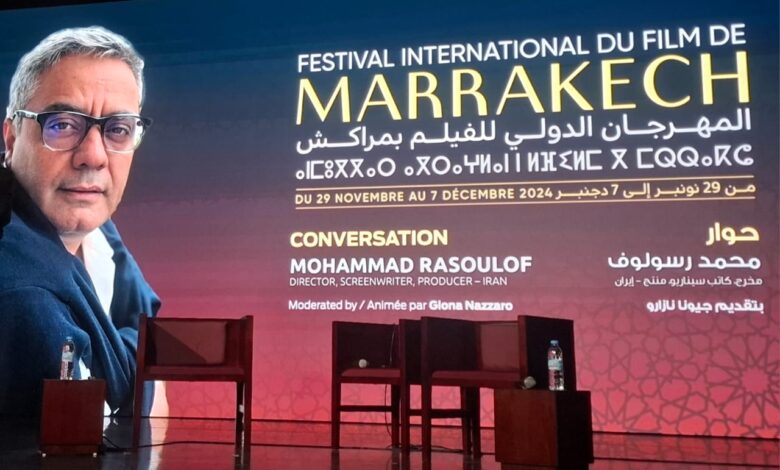

“The Sacred Fig Seed” by Director Mohammad Rasoulof : An Expertly Curated Iranian Cinematic Offering for the Marrakech International Film Festival Audience

By Safaa Ahmed Agha

As always, the 21st edition of the Marrakech International Film Festival succeeds in bringing some of the most outstanding and powerful films from Arab and international cinema to the eager Marrakech audience. This audience, consistently passionate, now accepts no less than the high-quality cinema it has grown accustomed to, both in technical and performance aspects.

The festival management, generous in its program this year, has presented a carefully selected Iranian masterpiece by the renowned global filmmaker Mohammad Rasoulof. His work, “The Sacred Fig Seed,” was served to the audience on a harmonious narrative platter, allowing viewers to journey through three hours of captivating cinema without weariness or boredom. This was achieved through a strong and meticulously refined visual style, where shots alternate between calmness and drama, showcasing Rasoulof’s ability to use cinematography to express complex emotions and ideas effectively. He relies heavily on natural lighting and unconventional angles, creating simple yet profoundly impactful scenes.

Rasoulof, the writer and director of “The Sacred Fig Seed,” attempted to tell his story in a deep and engaging manner, presenting it from an unconventional and striking perspective. Instead of delving into the gruesome details of prisons and torture chambers—which many viewers might find unbearable to watch—he shifted the intense events to the setting of a simple, financially comfortable family consisting of a husband, a wife, and their two young daughters. This demographic represents a segment of society seen as instrumental for change, one that ignited massive protests after the announcement of the death of an Iranian Kurdish girl, “Amasa Amini,” allegedly tortured by the “morality police” for “improperly wearing the hijab.” Authorities claimed she died of a stroke.

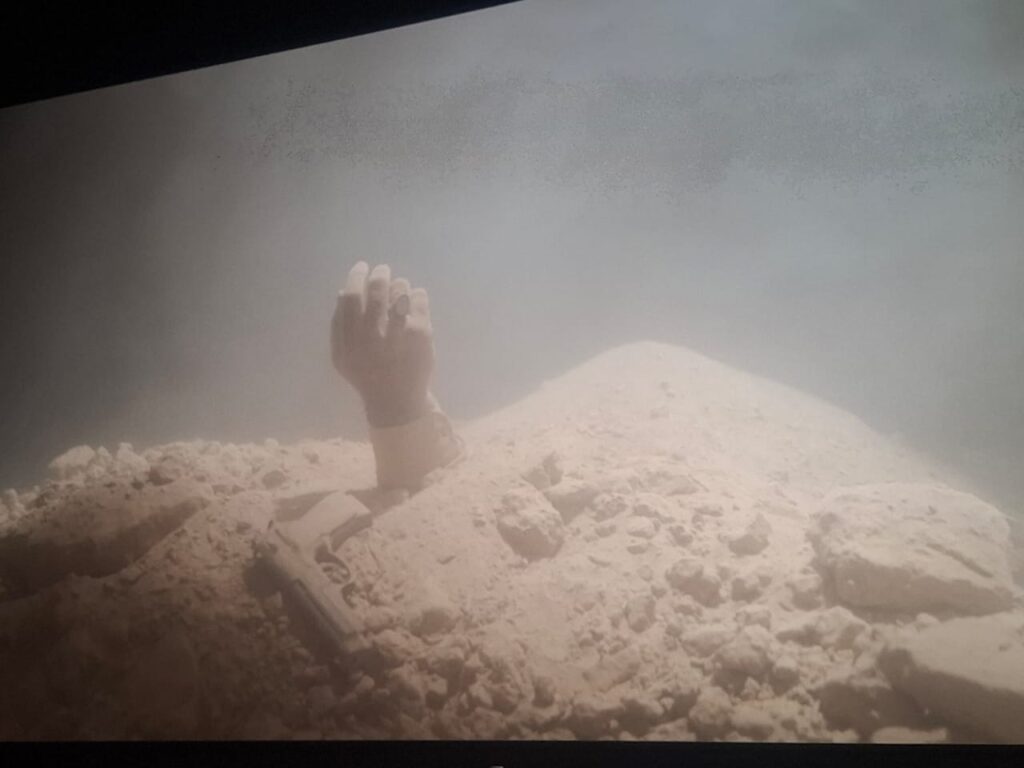

Throughout the film’s timeline, we witness the spread of protest fires and the oppressive crackdown by the authorities. This tension slowly and quietly moves inside the home of a man recently promoted to the rank of investigator within one of Iran’s security apparatuses. Ultimately, we see him applying the same practices he inflicts on foreign detainees to those closest to him. Thus, the family members discover the true face of this father who had once feigned idealism. He soon collapses under the weight of questions from his daughters, revealing himself to be entirely subservient to the regime he loyally serves. Although he claims that everything is under control, the family home—meant to be a place of peace and comfort—is transformed into a makeshift interrogation center and courtroom lacking the slightest standards of justice or trust between the “accused” and a system supposedly protecting everyone by rule of law.

Dim lighting, damp and cold spaces where the ironically named father “Iman” (Faith) detains his wife and daughter, along with the use of cameras during recorded interrogations—resembling confession sessions—recall the oppressive security vocabulary Iman employs daily in his work. Although he had been the ideal father, providing his daughters with all a girl might need in a conservative society, his transformation reveals the underlying tyranny he perpetuates.

The film’s events accelerate toward an inevitable tragic end, chosen by a so-called “paternal” authority that claimed to be the most righteous and in control.

As for the “fig seeds” referenced in the film’s title, they may symbolize the social and political transformations unfolding in Iran, where rejection of oppression intensifies despite the harsh, violent responses by the authorities to demands for change. Over time, these seeds become a symbol of the unwavering belief in the change destined to come. The seeds are clearly represented by the daughters and the mother, who shift from a family environment loyal to the regime to opposing it and supporting the protests growing by the day. They become new seeds, perhaps weak now, but certain to grow despite the dominance of repression and security forces.

The festival also hosted a master class with the director prior to the film’s screening, highlighting his importance and the weighty subjects he addresses, as he seeks to convey the plight of his oppressed people to the world through his cinema—a form of soft power influencing societies.

Mohammad Rasoulof is a director known for his brand of cinematic realism. His works cast light on social nuances that fall outside the logic of a religious regime controlling every aspect of life in Iran. He is also politically opposed to the regime’s tactics in dealing with dissidents. His film was selected to participate in the 77th Cannes Film Festival in southern France and he previously won the Golden Bear Award at the 2020 Berlin Film Festival for his anti-execution film “There Is No Evil.”

During the master class, he stated, “Recently, I have been sentenced to five years in prison. According to my lawyer, I have also been sentenced to flogging, a fine, and the confiscation of my property. This forced me to escape the clutches of the authorities there and head to Germany.” The charges brought against him included encouraging citizens to protest and calling for the state to abandon the use of violence and weapons against those resisting its dominance.

This escalating, threatening judgment reveals the challenges faced by artists in Iran when expressing their opinions or discussing social and political issues. Such challenges mirror the tension between art and censorship in Iranian society—one that has grown weary of the clerical regime’s control—especially in light of the widespread protests that have swept across the country, met by violent crackdowns, arrests, and escalations by security forces and police.